Il Reframing nel Design Thinking: uno strumento iterativo per ottenere le risposte giuste

Scoprite come il reframing offra prospettive diverse sui problemi aziendali. Questa abilità perspicace e iterativa vi garantisce di trovare le domande e le risposte giuste.

Il reframing è un’abilità iterativa e di problem solving polivalente che può essere utilizzata per riposizionare o spostare il problema centrale di un progetto all’interno di un processo di innovazione strutturato.

Una citazione tradizionale nelle metodologie di progettazione e ricerca afferma che il peggior errore possibile negli affari è “ottenere la risposta giusta alla domanda sbagliata”.

Questo è esattamente ciò che si combatte con il reframing e il suo scopo: un potente strumento di problem solving per assicurarsi di arrivare alle domande giuste e di affrontarle correttamente.

Continuate a leggere e scoprite come riorganizzare i vostri progetti utilizzando questa capacità di cambiare le carte in tavola per riscoprire il problema e risolverlo meglio.

Cos’è il Reframing

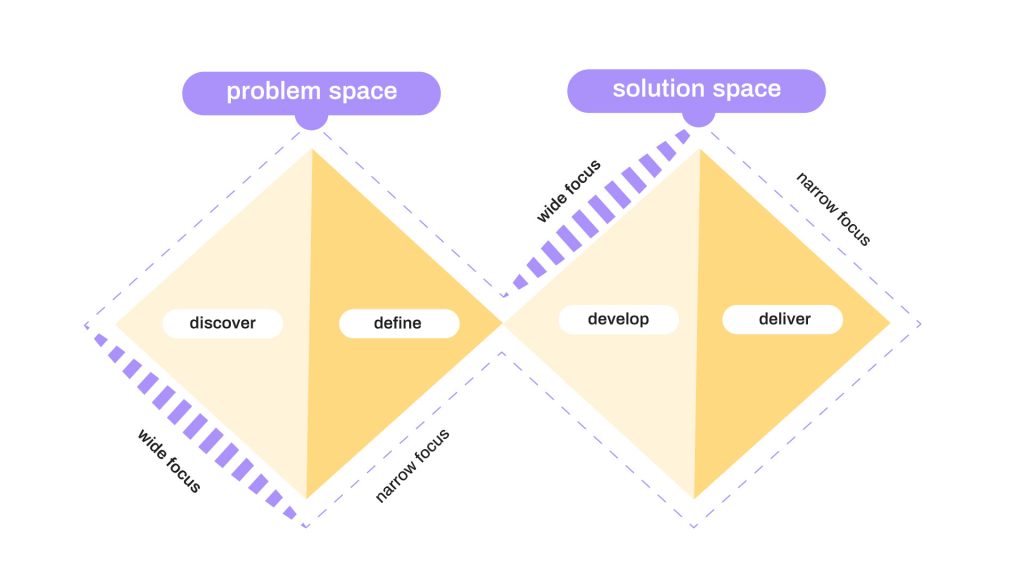

Il reframing è un potente strumento di problem solving che ci assicura di arrivare alle domande giuste e di affrontarle correttamente. Si usa durante il punto di svolta della fase di scoperta di qualsiasi processo di innovazione strutturato. Quel momento in cui si conducono interviste, ricerche approfondite e si utilizzano tecniche di analisi dei dati per comprendere il contesto e le sfide del problema.

Qui in MJV lo usiamo alla fine della fase di immersione del processo di Design Thinking.

Il reframing consiste nell’esaminare i problemi o le questioni irrisolte all’interno di un’azienda da diverse prospettive e angolazioni. Ciò consente di decostruire le convinzioni e le ipotesi degli stakeholder, rompendo i loro schemi di pensiero, per aiutarli a cambiare i paradigmi aziendali e a fare il primo passo verso soluzioni innovative.

Un problema non può essere risolto con lo stesso tipo di pensiero che lo ha creato, per questo il reframing dovrebbe essere usato come primo passo per generare soluzioni innovative. È utile anche come passo iniziale nel miglioramento di prodotti, servizi e/o processi, in quanto consente di affrontare il problema con nuove prospettive.

Un esempio pratico di reframing: il problema dell’ascensore lento

Immaginate una situazione ipotetica in cui siete responsabili della manutenzione degli ascensori di un edificio e dovete agire per rispondere al seguente reclamo:

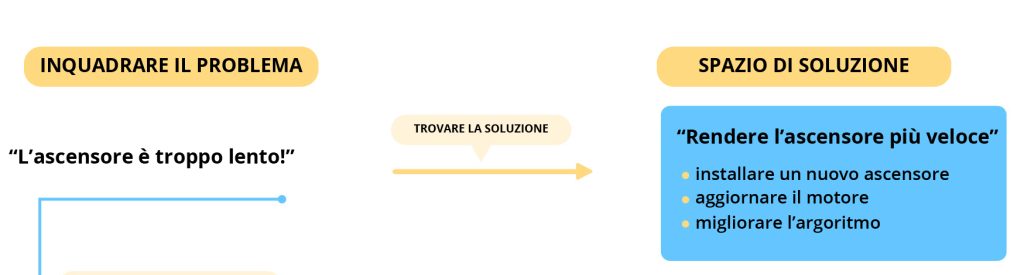

“Gli ascensori sono troppo lenti”.

Le risposte più ovvie per una possibile soluzione vanno da:

Installazione di un nuovo sollevatore. Aggiornamento del motore. Miglioramento dell’algoritmo.

“Questi suggerimenti rientrano in quello che chiamiamo spazio delle soluzioni: un gruppo di soluzioni che condividono le ipotesi sul problema” – dice HBR.

La domanda è: affrontano davvero il problema?

Ora, supponiamo che voi, in qualità di professionisti competenti che si occupano del problema, manteniate aggiornata la manutenzione dell’ascensore. In questo contesto, installare un nuovo ascensore al posto di uno funzionante non ha senso.

Anche la potenza del motore non sembra essere il problema, in quanto ne comporterebbe il mancato funzionamento (totale o parziale).

Infine, se l’algoritmo fosse rotto, avremmo qualche decina di persone imprigionate nei loro piani, perché l’ascensore girerebbe in continuazione senza mai arrivare a destinazione.

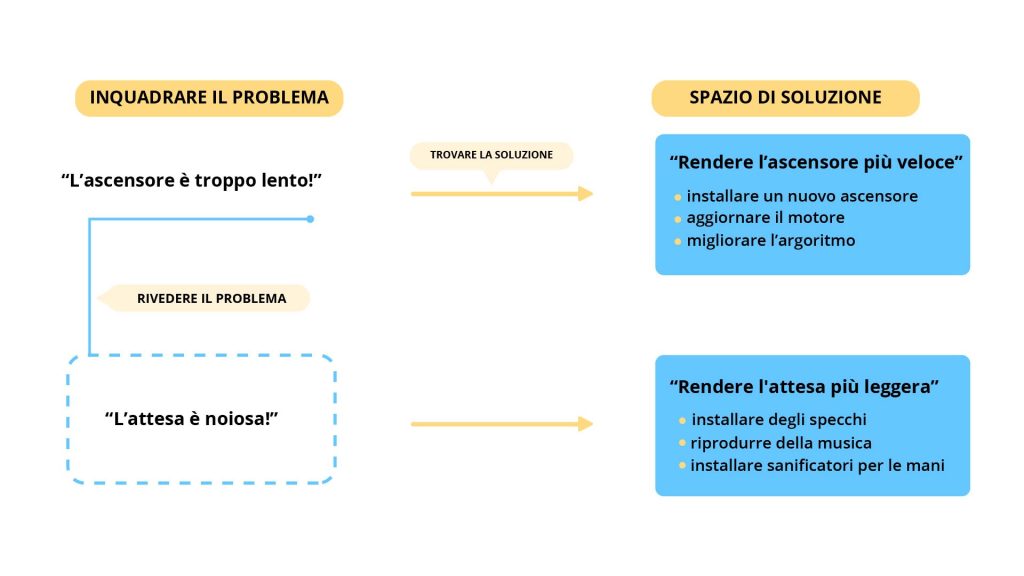

Dobbiamo riformulare il problema per scoprire cosa infastidisce davvero le persone. Ed è legato alla velocità.

Il problema non è che gli ascensori sono troppo lenti. È che la gente sente che gli ascensori sono troppo lenti. E la gente si annoia. Una cosa semplice come l’aggiunta di uno specchio non renderà gli ascensori più veloci, ma inizierà a vedere meno lamentele per la lentezza degli ascensori.

Questa riformulazione è piuttosto interessante perché non è una soluzione al problema dichiarato. Si concentra su ciò che realmente infastidisce le persone: l’attesa. In ogni situazione, non solo all’interno degli ascensori o nell’attesa.

“Si noti che l’inquadramento iniziale del problema non è necessariamente sbagliato. L’installazione di un nuovo ascensore probabilmente funzionerebbe” – HBR.

Ma sarebbe più economico, pratico e veloce? Questo è il punto di svolta.

Questo esempio è apparso per la prima volta nel libro “Systems, Organizations, and Interdisciplinary Research”, General Systems, vol. V (1960), di Russell L. Ackoff. In seguito è diventato parte degli articoli della rivista Harvard Business Review del 2017.

Come si applica?

Il processo si svolge in 3 diversi cicli: cattura, trasformazione e preparazione, che si ripetono fino al raggiungimento dell’obiettivo – stimolare i soggetti coinvolti a vedere i problemi sotto ottiche diverse – creando una nuova comprensione del contesto che porta all’individuazione di percorsi innovativi.

Di solito il team di progetto agisce da facilitatore in un processo che può durare da diverse settimane a un singolo workshop. L’importante è che si svolgano incontri con gli attori, che verranno interrogati con piccoli compiti che incoraggiano nuovi modelli di pensiero.

I cicli di riformulazione

Cattura

Si tratta della raccolta di dati sulla ragion d’essere del prodotto/servizio/azienda in relazione alle credenze e alle supposizioni dell’interlocutore che verranno utilizzati nella fase di trasformazione.

Questo ciclo si svolge di solito durante incontri o riunioni con gli attori coinvolti nel processo che, di solito, vengono interrogati (intervistati) sull’innovazione, ma possono anche essere istigati a svolgere esercizi di analogia, recitazione o altre attività dinamiche che mirano a rivelare un’altra prospettiva sulla questione.

Trasformazione

Con questi dati in mano, la trasformazione viene eseguita dal team di progetto, che ha il compito di mappare i dati raccolti durante la fase precedente e di aggiungere nuove prospettive. In questa fase si possono applicare diverse tecniche, come le mappe mentali, il viaggio, la negazione ecc. a seconda dell’obiettivo, del tipo di cliente e del momento del processo.

Preparazione

La preparazione è il momento in cui vengono creati materiali di sensibilità all’impatto, basati sui risultati della fase di trasformazione, che stimolano l’interlocutore a riflettere. Spesso vengono sollevate questioni che non sono state chiarite e vengono sviluppati/scelti strumenti per il ciclo successivo (ritorno all’acquisizione).

4 punti per il successo del processo di riorganizzazione:

- Offrire un ambiente rilassato, dove il cliente è invitato a rilassarsi e a ripensare al proprio lavoro.

- Creare discorsi che siano conflittuali ed emotivi, pieni di esempi di storie reali, per facilitare la comprensione di ciò che viene proposto.

- Offrire, alla fine di ogni sessione, materiale che permetta al cliente di trasmettere (all’interno e all’esterno dell’azienda) ciò che ha sperimentato e imparato nelle sessioni di generazione.

- Scegliete un facilitatore in grado di provocare il cliente, di fornire una nuova comprensione dei problemi iniziali e di trasformare un futuro incerto in qualcosa di plausibile.

Il reframing è ancora essenziale

MJV applica questa tecnica nella maggior parte dei suoi progetti. Ciò accade perché il punto di vista esterno, più imparziale e libero da preconcetti sui problemi, unito a un’indagine approfondita delle sfide e a opinioni diverse, crea una prospettiva diversa dei possibili percorsi verso la soluzione.

Spesso gli stakeholder credono che la sfida più grande sia esterna, mentre in realtà proviene dall’interno, dalla cultura aziendale. Altre volte, invece, è il contrario. In questo caso, attraverso la prototipazione rapida e la sperimentazione di nuove soluzioni di Design Thinking, è possibile trovare nuove sfumature per l’innovazione in modo molto agile.

Back